Alexxander Ziegler, Looking for dumbo, 2017–2020 (production still)

We think of science and art as antagonistic domains. Scientists aspire to make their knowledge production impartial, objective, and they deploy standardized methodology and procedures in the pursuance of this aim. Artists, by contrast, are seen to represent their own partial, idiosyncratic vision, that relies on subjective introspection, experience and sensitivity in following what they extract from the matters they are dealing with. As such, science is not art, and art certainly not science. neither one, however, is independent of the other either. Instead, art might slide into the cracks that science cannot reach by definition of its aims and methods.

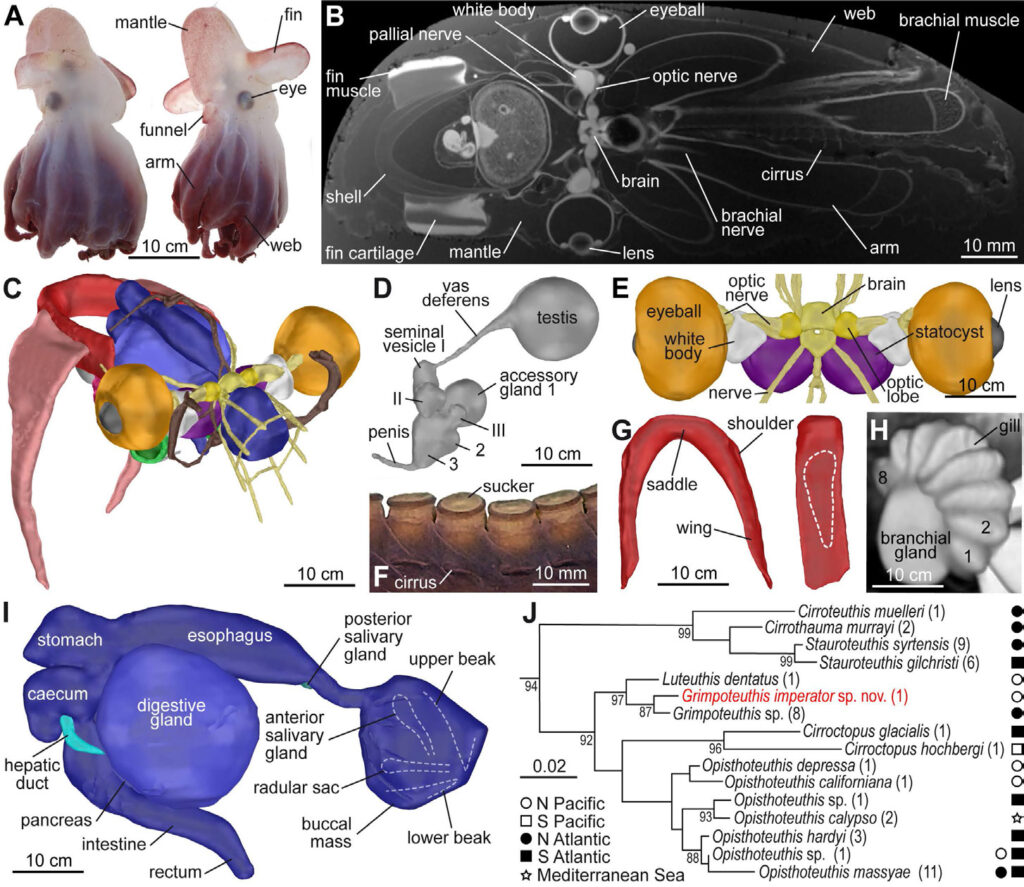

Alexander Ziegler develops non-invasive imaging techniques to reveal and study the evolution of anatomy and morphology, the bodily structures and organization, of invertebrates — animals that are free from the restrictions of a spinal column, although the techniques can be deployed, of course, on any animal (and plant and object). In 2016, Alexander and christina Sagorny discovered a new dumbo species, soon to be named Grimpotheutis imperator. Within the analytic images of the creature, art and science come to intersect. Produced with scientific aims in mind, what do they tell us once we look at them as we would look at an artwork? And what do these “scientific” images change about the ways we extract the octopus, or perspectives of her, from the artworks that surround them? It is a premise of this exhibition to trial this — we do not claim to have an answer.

Yet the images no longer appear exclusively scientific. the specimen morphs into a portrait, maybe of a murder victim, or a delinquent. Magnetic resonance scans bring the specimen alive in front of our eyes. three-dimensional micro-computed tomography abstracts our focus from the creatures’ outward appearance to reimagining her from within. If only they wouldn’t have to be removed from their homes and sedated.